Allah (God)

This article or section is being renovated. Lead = 3 / 4

Structure = 3 / 4

Content = 4 / 4

Language = 4 / 4

References = 4 / 4

|

According to Islam, Allāh is the creator of the universe. In the pre-Islamic era, the Quranic mushrikeen worshipped Allah as the supreme creator god, along with one or more lesser deites. A number of pre-Islamic gods and godesses are named in the Quran, for example Allāt (often transliterated as al-Lat based on one possible etymology[2][3][4]) Manāt, and al-‘Uzzá were Allah's daughters. One of the Five Pillars of Islam is to accept that Allah is the only God (Arabic: la ilaaha il Allah)[5][6]

Twenty-first century academic scholarship has considerably transformed our understanding about the history of the name Allah, his worship in Arabia, and the beliefs of the mushrikeen who are mentioned so often in the Quran. This progress has largely been made thanks to archaeological and epigraphic expeditions to Arabia to learn more about the history of the language, scripts and beliefs of Arabia in the centuries before Islam.

God is a deity in theist and deist religions and other belief systems, representing either the sole deity in monotheism (e.g. the Judeo-Christian Yahweh), or a principal deity in polytheism (e.g. the Hindu Brahman). God is most often conceived of as the supernatural creator and overseer of the Universe.

History of the name Allah and the Basmala

The Book of Idols by Hisham ibn al-Kalbi (d. 819 CE) is a series of distantly remembered folk tales describing the outright idolatry of the pre-Islamic Arabs, with an overall narrative that this came to an end with the rise of Islam. Academic scholarship today recognises this as a false narrative, serving to bring the immediately pre-Islamic period into a sharper contrast with Islam.[7][8] Our understanding of the religious landscape in pre-Islamic Arabia is being transformed in the 21st century by the study of epigraphic evidence (inscriptions on rocks, rock art, and their archaeological contexts), complemented with careful study of Quranic internal evidence and early Islamic sources, independent of later histographic works.

From the fourth century CE when Himyar began to embrace Judaism, pagan deities almost completely disappear from the epigraphic record of the South Arabian script family, commencing what is known as the monotheistic period in that southern part of Arabia. In their place, a single god, Rḥmnn (literally, The merciful) starts to appear, which eventually becomes the Quranic epithet al-Rahman (more on this below).[9] Professor Ahmad al-Jallad, who is renowned for his work on the languages and writing systems of pre-Islamic Arabia, notes that the name raḥmān appears in a number of south Arabian pre-Islamic inscriptions and is derived from Jewish Aramaic raḥmānā.[10] Sigrid Kjær observes that the use of Rahman (or Rahman-an including the definite article suffix) becomes truely monotheistic only in the sixth century CE, previously used in a monolatric context (the sole object of worship, even while other deities are acknowledged). The Quran has a chronological progression in the use of theonyms, with Rabb (lord) in the earliest phase, then al-Rahman, and later an almost exclusive use of the name Allah.[11]

The word Allāh first appears in the epigraphic record as the name of one of many Nabataean deities in 1st century BCE or 1st century CE northern Arabia.[12] The word possibly might have come from a contraction of al-ʾilāh (the god), though there are some linguistic difficulties with this idea. In any case it was the name of a deity at that time and there is no indication that it was associated with the monotheistic Judeo-Christian god. The name Abd Allah (like the name of Muhammad's father) first appears in a Nabataean pagan context. There they used the same construct also for other gods, for example ʿAbdu Manōti, "servant of Manāt". In Safaitic inscriptions (a script used in the north Arabian desert), the name Allāh is occasionally invoked, though other deities much more so. By the sixth century CE the name Allāh is applied in a monotheistic context around the Hijaz and at some point merges with the Christian al-ʾilāh (the god). Allah appears equated with al-Rahman (who in the south was associated with the Judeo-Christian God) in a pre-Islamic basmala inscription discovered in Yemen, as discussed in the next section below.[13] Al-Jallad writes, "In contrast to South Arabia, the North Arabian monotheistic traditions of the 5th and 6th c. CE invoked al-ʾilāh/allāh. While al-ʾilāh is attested in clear Christian contexts, allāh is rarer and found in confessionally ambiguous contexts. It is impossible at this moment to decide whether the distinction between the two was simply regional or whether it betokened a confessional split. What is clear, however, is that “Raḥmān” was not used in pre-Islamic times in North Arabia."[14]

The Basmala

The Islamic bismillah, "In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful" (Bismillah Ar-Rahman Ar-Raheem), is recited before the start of each surah and begins the al-Fatiha prayer. Within the surahs themselves, it occurs once only, in Quran 27:30.

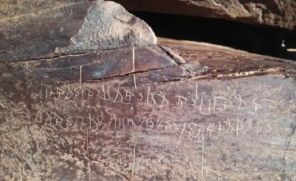

In 2018 the first known pre-Islamic Basmala inscription was found on the side of a cliff in Yemen, reading in South Arabian Script, "In the name of Allah, Rahman; Rahman lord of the heavens" (bsmlh rḥmn rḥmn rb smwt). The rest of the inscription reads, "satisfy us by means of your favor, and grant us the essense of it (i.e. wisdom) to number our days". Writing about the discovery, Ahmad al-Jallad dates the inscription to the late 6th or early 7th century CE and observes that overall the inscription has a psalm like quality, likely impacted by Jewish or Christian liturgy. He interprets the second rḥmn as rḥm-n ("have mercy on us")[15] He also notes that al-Rahman was originally a distinct deity to Allah, and not a mere descriptor of him seen in the Islamic basmalah. Maslamah, a Yemenite rival prophet to Muhammad, worshipped al-Rahman, the deity of ancient Himyar. Al-Jallad proposes that the basmala was used to synchronize the two monotheistic poles of Arabia, Allah in the north (where other deities completely disappear from the epigraphic record by the sixth century CE) with al-Rahman in the South. This equivalence was probably introduced during the Himyarite northward excursions in the sixth century. This regional difference is echoed in Quran 17:110. Ar-Raheem (the merciful) would then be an Islamic innovation appended to al-Rahman of the pre-Islamic Basmala which by then had come to represent an adjective describing Allah. [16] This pre-Islamic basmala and many other pre-Islamic inscriptions bear similarities with phrases and terminology found in the Quran.[17] Rb smwt in the inscription ("Lord of the heavens") is similar to South Arabian inscriptions in the Sabaic language (mrʾ smyn w-ʾrḍn) a phrase which appears also in verses such as Quran 19:65 ("Lord of the heavens and the earth"; rabbu l-samāwāti wal-arḍi).[18]

Spelling

Allāh is written lh in this pre-Islamic basmalah inscription found in Yemen, which is a spelling also found in north Arabia where bilingual Safaitic-Greek inscriptions confirm it was vocalised as allāh.[15][12] In 2022, an expedition by al-Jallad together with Hythem Sidky discovered that in 6th to early 7th century pre-Islamic inscriptions, the spelling on inscriptions between Medina and Tabuk is ʾlh (which was also the Nabatean spelling), or lh, or when used in construct (iḍāfah), lhy. However, the double lām spelling ʾllh occurs on inscriptions in the region between Mecca and Taif, which is significant in terms of the spelling found in the Quran. In terms of orthography, the double lām spelling of allāh as found in the Quran is an unusual orthographic practice, since in semitic scripts a doubled consonant is not written twice.[19][12]

Beliefs of the Quranic Mushrikeen

Historian Patricia Crone in a detailed article on the Quranic mushrikeen pointed out that they believed in Allah as the Judeo-Christian creator god, but associated with him one or more lesser partners, usually described as gods but sometimes his offspring, and that he took female angels for himself. Sometimes these gods are named, most of which have also been found in rock inscriptions. The mushrikeen also believed in jinns and demons, and some worshipped heavenly bodies. Ahab Bdaiwi adds that only rarely is outright paganism found of the kind described in later sources (like Ibn al-Kalbi).[20][21][22]

Theology

Oneness

Tawheed (also spelled tawhid) is the Islamic monotheistic concept of god. Although the concept of monotheism is intrinsic to tawheed, tawheed encompasses more than the concept of god simply being one. It also refers to all of the implications of the existence of one god who created the universe and has very specific wishes for his creations. It stands in contrast to shirk in all of its forms.

Attributes

The earliest Islamic school of theology was formed by the Mut'azila, who applied a rationalist approach to understanding the Quran. In their view, Allah's attributes (including Quranic references to body parts) were to be understood metaphorically. For example, God's 'hands' are his blessing, God's 'eyes' are his knowledge, his 'face' is his essence and his seating himself on his throne is his omnipotence. When Quran 75:22-23 says that on the day of resurrection the believers will "see" Allah, the Mut'azila said they will see him with their hearts. In contrast. Al-Ash'ari (d. 936 CE) who founded the most dominant school of Islamic theology disgreed strongly with the Mu'tazila, arguing that rather Allah's attributes are real and believers will see him with their eyes on the day of resurrection, though his body is not like a human body and it is not possible to rationally understand what is meant by such verses in the Quran. Maturidi's (d. 944 CE) doctrines were similar to al-Ash'ari with subtle diffences, in this case that the believers will see Allah with their eyes but not comprehend him, and that when the Quran said Allah sat upon his throne this had to be taken as literally true.[23][24]

References

- ↑ Ahmad al-Jallad (draft) The pre-Islamic basmala: Reflections on its first epigraphic attestation and its original significance, pp. 3, 6

- ↑ Arne A. Ambros, and Stephan Procházka - A Concise Dictionary of Koranic Arabic (p. 306) - Weisbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, 2004, ISBN 3895004006

- ↑ Lat, al- - Oxford Islamic Studies Online

- ↑ Regarding the possibility that Allāt was a contraction of al-'ilāhat, meaning "the goddess", Dr Marijn van Putten, a leading expert of Arabic linguistic history, notes it would be a completely irregular contraction and evidence is marginal or non-existent. Regarding the possiblity that it originated as a feminine form of Allāh, he finds it quite likely that there is no relation whatsoever. See this Twitter thread involving Dr van Putten - 30 October 2022

- ↑ Shahada - Encyclopedia of the Middle East.

- ↑ Embracing Islam - The Modern Religion

- ↑ See the introduction of the open access chapter: Ahmad Al-Jallad (2022), The Religion and Rituals of the Nomads of Pre-Islamic Arabia: A Reconstruction based on the Safaitic Inscriptions in (ed. Zhi Chen et al.), Ancient Languages and Civilizations, Volume: 1, Leiden: Brill

- ↑ Patricia Crone' The Religion of the Quranic Pagans: God and the Lesser Deities, Arabica 57 (2010) p. 171 ff.

- ↑ See p. 122 in Ahmad al-Jallad (2020) Chapter 7: The Linguistic Landscape of pre-Islamic Arabia - Context for the Qur’an in Mustafa Shah (ed.), Muhammad Abdel Haleem (ed.), "The Oxford Handbook of Qur'anic Studies", Oxford: Oxford University Press

- ↑ "He further writes "In South Arabia, the divine name rḥmnn/raḥmān-ān/ ‘the Raḥmān’ refers to the deity of the monotheistic period, which was heavily influenced by, or even derived from, Judaism and, thus, is likely a loan translation of rḥmnʾ.

Ahmad al-Jallad (draft) The pre-Islamic basmala: Reflections on its first epigraphic attestation and its original significance, pp. 7-8 - ↑ Kjær, Sigrid (2022). ‘Rahman’ before Muhammad: A pre-history of the First Peace (Sulh) in Islaw, Modern Asian Studies, 56(3), 776-795. doi:10.1017/S0026749X21000305

"It is salient to point out that, based on an approximate chronological dating of the Quranic suras, theonyms in the Islamic scripture seem to have evolved in three phases. In the earliest phase, the Quran uses rabb, shifting to al-Rahman, and finally culminating in an almost exclusive use of Allah in the later suras. Rabb simply meant ‘Lord’ and was used for immanent betylic divinities. Its use in the earliest parts of the Quran also corresponds to a monolatric and immanentist usage. By contrast, al-Rahman was clearly associated with Moses in the Quran and the rejection of image-worship, which appears in later Meccan verses. Eventually, however, Allah became the universal theonym, subsuming both Rabb and al-Rahman, in the service of an Abrahamic and fully biblicized monotheism that took shape in Medina."

In a footnote Kjær adds: "The initial reluctance to use the theonym Allah might have been due to its polytheistic origins.", citing Böwering, Gerhard, ‘Chronology and the Qur’ān’, in Encyclopaedia of the Qur’ān (Leiden: Brill, 2001), p. 329 - ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 See the start of Appendix 1 (p. 93) in the open access chapter: Ahmad Al-Jallad (2022), The Religion and Rituals of the Nomads of Pre-Islamic Arabia: A Reconstruction based on the Safaitic Inscriptions in (ed. Zhi Chen et al.), Ancient Languages and Civilizations, Volume: 1, Leiden: Brill

- ↑ See this twitter thread by leading linguist in the history of Arabic, Dr Marijn van Putten - 19 October 2021 (archive)

- ↑ Ahmad al-Jallad (draft) The pre-Islamic basmala: Reflections on its first epigraphic attestation and its original significance, page 14

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Ahmad al-Jallad (draft) The pre-Islamic basmala: Reflections on its first epigraphic attestation and its original significance, pp. 6-7

- ↑ Ahmad al-Jallad (draft) The pre-Islamic basmala: Reflections on its first epigraphic attestation and its original significance, page 13 ff

- ↑ Ahmad al-Jallad (2020) Chapter 7: The Linguistic Landscape of pre-Islamic Arabia - Context for the Qur’an in Mustafa Shah (ed.), Muhammad Abdel Haleem (ed.), "The Oxford Handbook of Qur'anic Studies", Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 121 ff

- ↑ Ahmad al-Jallad (draft) The pre-Islamic basmala: Reflections on its first epigraphic attestation and its original significance, page 8

- ↑ See 18 to 27 minutes in Ahmad Al-Jallad II: The History of Pre-Islamic Arabia based on Epigraphic Evidence - youtube.com - 20 March 2023

- ↑ Patricia Crone' The Religion of the Quranic Pagans: God and the Lesser Deities, Arabica 57 (2010) 151-200

- ↑ See Dr Ahab Bdaiwi's blog post summarizing his findings Arabian Monotheism before Islam: Some Notes on the Mushrikūn of the Qurʾan - 26 October 2021

- ↑ See also this earlier Twitter.com thread by Dr Ahab Bdaiwi - 12 August 2020 (archive) and this one - 26 May 2021 (archive)

- ↑ Fitzroy Morrisey (2022) A short History of Islamic Thought, UK: Head of Zeus, ISBN: 9781789545661, pp.65-69

- ↑ Ash'ariyya and Mu'tazila - Muslimphilosophy.com