Seven Sleepers of Ephesus in the Quran

This article or section is being renovated. Lead = 4 / 4

Structure = 4 / 4

Content = 4 / 4

Language = 4 / 4

References = 4 / 4

|

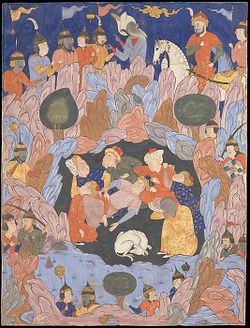

The Qur'anic story of the "Companions of the Cave" has traditionally been explained by the Islamic narrative as proof of Allah's divine power whereby he miraculously caused 7 youths to fall asleep and awaken after more than 300 years. Yet comparison with the literary milieu of the Qur'an, 7th century Chrisian culture in the Middle East, reveals parallels to the 7 Sleepers of Ephesus, a Christian legend dating from the 5th century which tells the story of Christian youths being persecuted by the pagan Roman Emperor Decius in the 3rd century. The youths seek shelter in a cave, fall asleep for over 200 years, and venture out only to find that the Empire is now Christian. Their faith confirmed, the youths then die and are embraced by the Lord. Rather than a mere exhibition of god's power, the original story was a parable meant to emphasis the ability of Christian faith to overcome persecution, a celebration of the Christianization of the Roman Empire and an answer to heretics at the time of the story's composition who doubted the literal nature of the physical Resurrection. As the Qur'an does not preserve the entire story, but appears to merely refer to it, the mufassirun of later generations misinterpreted the story, leaving out key components and failing to relay the underlying message of the original parable. In 2023, academic scholar Thomas Eich published his finding that the specific version of the tale found in the Qur'an overlaps significantly with the version taught by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Theodore of Tarsus (d. 690 CE), and which can be situated in an early 7th century Palestinian context.[1]

Introduction

The story of the companions of the cave is found in the 18th surah of the Qur'an, al-Kahf (the Cave), for which the surah is named. It relates the tale of a young group of believers, who fall into a supernatural sleep in a cave, only to awaken hundreds of years later. This story mimics a story found in the Syriac homily by a Christian bishop named Jacob of Serugh (521 CE).[2] His story tells of seven young Christians in Ephesus (an ancient Greek city now situated in modern-day Turkey), who hide from an evil emperor in a cave, fall into a supernatural sleep for hundreds of years, and awaken to find that their home town has been converted to Christianity.[3]

Christian and Jewish Legends in the Qur'an

It is well known that the Qur'an contains many stories that were first told in Jewish and Christian communities around the Middle East. This includes apocryphal and legendary tales that originated in Syria between the 2nd and early 7th century CE. One of the most widespread of these stories was the legend of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus. Popular in both Europe and the Middle East during medieval times, this story was translated into Latin and found its way into many Christian works of that era. It also became very prominent in the Muslim world because of its inclusion in the Qur'an. After the Renaissance and Enlightenment of the 16th century, this story fell out of favor and was largely dismissed as mythical. Since the tale is not found in the Bible, it was also rejected by the majority of the world's Christian churches without any theological consequence. The feast day for the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus is no longer observed by the Roman Catholic Church (it is now referred to within the church as a "purely imaginative romance"), and the story today is virtually unknown among the Protestant churches.

Oral Tradition

While it is impossible to know the exact details of how the author(s) of the Qur'an came to know the story of the Seven Sleepers, we do know that according to the Islamic narrative itself Muhammad had ample opportunities to hear it during his 62 year life. According to the traditional sources, Muhammad traveled to Syria while he was a caravan trader and he may have heard the story there. Visitors to Mecca would have included Syrian Christians, who would have known this popular story as well. Muhammad's followers also could have related this story after contact with Christian communities near the Mediterranean and in Arabia. In short, there were numerous ways in which this story could have be told to Muhammad during his lifetime.

Significant overlap with 7th century Greek-Palestinian version

As mentioned above, in 2023 academic scholar Thomas Eich identified a written version of the tale which had circulated in an early 7th century Palestinian monastic community and which significantly overlaps with the Quranic tale. In the abstract of his article he writes:

In his article (the rest of which is written in German), Eich explains that Theodore spent the period from the 640s until 668 CE in Rome in the Monastery of St. Anastasius, a Greek monastic community which had begun to move there from Palestine from the 630s, probably triggered by the Byzantine conquest of Palestine in 629-30, though possibly due to the Arab conquest several years later. In 669 the Pope sent Theodore to England to take the vacant seat as Archbishop of Canterbury, where his teachings would go on to reflect those of his former Greek-Palestinian monastic community and showed knowledge of the Syriac church fathers.

It is in a Biblical commentary by Theodore when he was in England (surviving in two 9th century and one 11th century Latin manuscripts) where we find a version of the seven sleepers story, quoted below, with exceptional correspondances to the Quranic version. Unlike all other Syriac-Christian references to the legend (which have all been assigned to communities in Palestine, and in one case to Najran in Southern Arabia), in Theodore's version:

- The cave is not walled up. Quran 18:18 likewise suggests that the cave was open.

- It has the dog motif. This appears likewise in Quran 18:18 and Quran 18:22, though is also very briefly mentioned in material for a pilgrim travel guide written by Theodosius between 518 and 530 CE.

- It mentions the emperor building a church over the site. Similarly, in Quran 18:21 the authorities build a masjid there.

Theodore's version appears to have Syriac origins. Eich points out that Theodore credits his story and its use in the context of Lot's wife to "eastern Fathers". Additionally, the only other Latin source to mention the church built over the cave is that of Gregory of Tours who credits his version to a translator from Syria. Finally, the fact that the story is used to answer a question about the soul of Lot's wife (whether it stays in the body until the day of resurrection) would have been of special interest in the region of Palestine, where a particular pillar of salt associated with her fate after the destruction of Sodom was a well known sight on pilgrimage routes at that time.

Theodore's version occurs in a section of his Biblical commentary on the Gospel of Luke. It is quoted below (machine translated from Eich's German article, which also includes the original Latin text).

Parallels with the Syriac version of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus

Prior to the identification of the above quoted Palestinian version, a number of clear parallels between the Qur'anic story and the legend of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus had already been identified, though also differences.

The two narratives clearly share many features which would indicate that they are in fact one and the same. They are virtually identical in the events they describe and both contain striking similarities in key details. Both story mention youths, a cave, a long sleep, buying bread with coins, and the Day of Judgement. Since the Syrian legend pre-dates the Qur'anic story by almost two centuries, it should be clear that the author of the Qur'an is simply retelling the Syriac story. The Qur'an even suggests in verse 18:9 that the audience is familiar with the story as they should have already "reflected" upon it and Quran 18:22 indicates that different views on the details of the story were in circulation.

Trouble

Both stories begin by stating that a group of youths are in trouble. While the Qur'an gives few details on the nature of their problem, the Syriac legend tells specifically of an emperor, named Decius, who was forcing Christians to make sacrifices to the pagan gods or else face death.

Inscription at the Cave

In the Qur'anic account, the author asks if the reader has reflected on the companions of the cave and their inscription. The inclusion of the word "inscription" is an important detail connecting the story of the Qur'an with the story of the Seven Sleepers. In the Syriac legend, we have a more detailed narrative that states that the story of the youth's martyrdom was written and laid near the entrance of the cave.

While the Qur'an does not mention the inscription again, it plays an important role in the Syriac story. The people who discover the sleepers use the inscriptions to verify the truthfulness of the seven men's story. This helps make sense of why the author of the Qur'an would mention this detail as part of what the reader should "reflect" upon.

Among early Qur'anic commentators, there seems to be quite a bit of disagreement on the exact nature of the word "ar-Raqim" which is translated as "inscription" by all the major English translators. Sa'id bin Jubayr, who is held in the highest esteem by scholars of the Shi'ite and Sunni Islamic traditions, has his opinion recorded In Ibn Kathir's classic Tafsir. Ibn Kathir relates that Sa'id bin Jubayr said that the "ar-Raqim" was indeed an inscription placed at the entrance of the cave. This confirms the direct connection to the Syriac legend.

Disagreement Over Time in Cave

In retellings of the Syriac legend, there is some dispute about the time the sleepers were in the cave. Apparently, this disagreement among Christians was still an issue in the 7th century when this story was first told to the early proto-Islamic Believer community. The Qur'an relates that Allah has woken the sleepers as a way to test who could calculate the length of their stay the best.

Youths

Another important detail between the two stories is that the companions are called "youths". This was likely a literary device in the original story to show that young people were more devout and fervent in their faith than older believers. Likewise, the Qur'anic story emphasizes their age as a polemic against those stuck in the same belief as their ancestors.

Perception of Time

Even though the young men sleep in the cave for hundreds of years, they think they have only slept just a day.

Money for Bread

Another similarity between the two stories is that both state that one of the companions goes to the city to buy bread with coins. The Syriac legend states that the name of the person who buys bread is Malchus.

Fear of Capture

While attempting to buy bread in town, Malchus is detained by town folk who are amazed that he has an ancient coin in his possession. He is fearful that the emperor and the town folk are pagans who will punish him. In the Qur'anic story, a companion warns the other to avoid capture out of fear that he will be forced back into polytheism.

Day of Judgement

Both the Syriac legend and the Qur'anic story state that the youth were awoken as a way to strengthen the faith of believers in the final Day of Judgement.

Place of Worship at Cave

The Qur'an states that a place of worship was built at the site of the cave after the events it describes. Interestingly, a church was built over the purported sight of the miracle in Ephesus. This cave was a destination for pilgrims for almost a thousand years. By the late 6th century, this church contained marble structures and a large, domed mausoleum.[6] This information would have been known to Christians in Syria and likely passed along to the author of the Qur'anic verses as well.

Number of Sleepers

The author of these verses in the Qur'an does not provide a definitive answer for the number of sleepers, stating the possibility that there were three, five, or seven. The Syrian legend clearly and emphatically states in the first sentence that the story is about seven sleepers.

Slept for Hundreds of Years

Both accounts state that the youths slept for hundreds of years. The Qur'an stating that it was 300 years and the Syriac version stating the number was closer to 200. There is considerable variation in different versions of the Seven Sleeper legend as to the time frame that they slept. Though all of them are longer than 200 years.

The Syriac account identifies the Emperor persecuting the seven young men as Trajan Decius, who reigned from 249 - 251 CE. Since the story first originated around the middle of the 5th century (circa 450 CE) a sleep of 200 years would be the more accurate number. Given this connection, some Islamic scholars and apologists in modern times have back-peddled on the number of 300 given in the Qur'an, re-interpreting it as a number given by the people at the time and not a definitive number given by Allah.

Differences with the Syriac version

While there are many similarities and they are clearly describing the same events, there are also a few key differences between the Quran and Syriac versions.

Vagueness of the Qur'an

The author of the Qur'anic account seems to be unclear on a few details. He refuses to give an exact number of sleepers, instead giving a vague range of numbers and says that only Allah knows the right number. He is not specific on the time frame, offering a number of years but nothing definitive. He does not mention any names, fails to mention where these events took place, and does not state when this story happened. This evidence suggests that the author was only vaguely familiar with the story and may not have had access to a complete, written copy; perhaps the story had been orally relayed to him.

Story's Purpose and Polytheism

The purpose behind the Syrian story appears to be the affirmation of a bodily resurrection on the Day of Judgement.[7] While the Qur'anic story makes references to the Day of Judgement, it does not mention a resurrection. In fact, the story's stated purpose is to "warn those (also) who say, 'Allah hath begotten a son'"[8] (i.e. Trinitarian Christians). The mainstream Islamic position concerning the Christian doctrine of the Trinity is that it constitutes an act of "shirk" (the sin of practicing idolatry or polytheism) and makes one a "mushrik" (polytheist).[9][10] So, the Qur'an has taken a story written by Christians and reworked it into a polemic against Christianity.

The Syrian narrative, in its content and structure, is successful in achieving its purpose. The youths awakening to find that their home town has been converted to Christianity is a compelling ending and the mere existence of the youths provides the affirmation of a bodily resurrection. This serves the double purpose of affirming the principle that god will save Christians through persecution, and also exulting in the Christianization of the Roman Empire that had once persecuted Christians. However, in the Qur'anic narrative the youths awaken to the same 'polytheists' and are only questioned by each other concerning the length of their sleep. There is no argument made for why Allah could not have begotten a son, nor an answer provided for what benefits the youths were meant to gain from their long sleep.

Historicity

Since it is found within the Qur'an, Islamic scholars and apologists have defended the historicity of the story.[11] However, there are significant reasons to doubt its historical authenticity. Not only is it scientifically impossible for the human body to live three hundred years but there is good evidence that this story may have been invented as a political and theological polemic within the Syrian Christian Church. These facts, along with connections to many pre-existing legends about sleeping heroes, strongly suggest that this story of the Seven Sleepers should be placed in the category of myth and legend.

Science

The longest-living person, whose dates of birth and death were verified to the modern standards of the Guinness Book of World Records and the Gerontology Research Group, was Jeanne Calment, a French woman who lived to the age of 122. The maximum recorded life span for humans has increased from just under 100 in the 18th century to 122 years in the 21st century; if we go back to the 7th century the maximum age was significantly less. Therefore, any account of humans living beyond a century should be viewed with immense skepticism. Dr. Mike Stroud, senior lecturer of Medicine and Nutrition at Southampton University in England, states that the "The average resting human body, doing absolutely nothing, produces about 100 watts of body heat, which could function a light bulb."[12] Without this heat and energy, cells will begin to decay and organs will fail. In order to maintain this energy, humans require food and water; after two months with no food and water, the human body would cease to function.[13] Even in a hibernation-like sleep, a three hundred year lifespan would be impossible.

Sleeping Hero Legends

There is a long tradition in ancient cultures of myths about the preservation of important heroes. One such example of this folklore comes from Persia. In their legends, immortals were ancient heroes who were kept in deep sleep until the doomsday, when they wake up to assist the appointed messiah to save the world of cruelty and injustice.[14] Often times these immortals were associated with the sacredness of the number seven; and many stories portrayed these saviors to be seven male figures.[15]

This legendary motif can be found in many Middle Eastern cultures as well, including Jewish and Christian traditions. The book of Maccabees, an apocryphal scripture that details the deeds of Jewish rebels who opposed Roman rule from 164 BCE to 63 BCE, contains the story of a pious mother and seven brothers. This family is persecuted by an evil king who forces them to eat pork. They refuse and are tortured to death rather than abandon their faith and Jewish customs. [16] These seven brothers were revered as saints for many generations, spawning cults dedicated to preserving their story. However, because Jews were persecuted and not popular by the 4th century, Christian variations of this legend began to circulate, including the story of St. Felicitas and her seven sons. Dr. Albrecht Berger, professor of Byzantine Studies at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat of Munich, affirms that there is a clear connection between these variations of the Maccabean story of seven brothers and the Christian legend of the Seven Sleepers, with the later being a clear adaptation of the Jewish story.[17]

The tradition of sleeping heroes continued beyond the 7th century. Dozens of examples of these types of stories can be found throughout medieval literature.[18] In more modern times, the story of "Rip Van Winkle", by American author Washington Irving (1819) portrays a man who climbs up into a mountain, falls into a magical sleep for twenty years, thinks only a day has passed, returns to his town to realize he recognizes nobody, and discovers that society has dramatically changed.

Origins of the Legend

While the complete story of the Seven sleepers was not first written down until the 6th century, the story was known in Syria by the middle of the 5th century. It is first mentioned by Bishop Stephen of Ephesus (c. 448-451 CE) [19] and it is also referenced by Bishop Zachariah of Mitylene (c. 465-536 CE).[20] During this time period, a number of theological controversies were taking place in Syrian Christian communities.[21][22] Among these was a debate over the nature of the resurrected body. Called the Origenist controversy, after the heretical Christian writer and cleric Origen, this theological disagreement began in Egypt during the late 4th century and by the middle of the 5th century had spread into Asia Minor. Origenists claimed that the resurrected body of the believer was not the same physical body they had during life. Stephen records that the bishops of his time regarded the miracle of the Seven Sleepers as a divine answer to the controversy. In his work, Zachariah of Mitylene uses the case of the Seven Sleepers as evidence toward defending the orthodox position on the resurrection:

It seems all too convenient that this miracle of physical preservation would suddenly occur right at the height of a theological controversy about the resurrection of the physical body. This naturally leads to skepticism of the historical nature of these events, rather pointing to the story being invented solely as a polemic for one side in a theological debate.

Grotto of the Seven Sleepers in Ephesus

Located just outside of the ancient city of Ephesus in Turkey, the Grotto is a network of catacombs, tombs, and graves around a cave on the eastern slope of Panayirdag hill. Archaeological evidence collected in the 1920s has verified that some of the tombs at the site in Ephesus date back to the middle of the 5th century but it also showed that the cave was in use at least two centuries prior. Among the items collected were pottery shards with Christian symbols along with inscriptions on the walls dedicated to to the seven sleepers. Other pieces of pottery contained images of Greek and Roman gods.[23]

While this evidence confirms that people living near Ephesus associated those buried at this site with the legend of the Sleepers; it does not confirm the actual events of the story. What it does show, is that the legend began sometime in the middle of the 5th century and this site was associated with the story around that same time. Historian Ernest Honigmann points out:

Whether this story has an historical core or not is still a matter of debate. However, the evidence appears to point to a speedy acceptance of the legend based more on the desire for it to be true rather than a measured evaluation of the evidence.

Abu Alanda in Amman Jordan

Located near Amman Jordan, this site has alternatively been identified as the one mentioned in Surah Al Kahf. It was discovered by the Jordanian archaeologist Rafiq Wafa Ad-Dajani in 1963 CE.[24] The cave and tomb have become a tourist destination and the locals refer to it as Al-Raqim, or the (cave of) the inscription. However, beyond local tradition, there seems to be little that links this site to the story of the Seven Sleepers.

The location does appear to be an old Byzantine-Roman burial site, but there are thousands of these across the region with almost 750 in just the Irbid–North Jordan Valley region alone.[25] These tombs often held the remains of multiple people and were usually situated in or around hillsides and caves. In fact, there are a number of similar rock-cut tombs in the area near this cave in Abu Alanda.[26] Without any kind of inscriptions or other identifying features, there is little reason to single out this particular site as the one mentioned in the Qur'an. Even the claims of a small ancient church, later converted into a mosque at the site, offer little supporting evidence as churches and chapels were commonly built near grave sites.

Other, spurious claims that the remains of seven individuals and a dog skeleton were found in the cave, along with the discovery of copper coins, cannot be verified as the archaeological work done in the 1960s did not definitely date the items at the site.[27] Human remains, coins, and jewelry are very common in all of the Byzantine tombs in the region.[28] Without proper dating, we have no way to verify if the remains at this site pre-date the Qur'anic story or if they were placed there at some point in the preceding 1,400 years. The cave only has four alcoves and sarcophagi, which implies it was never intended to hold the remains of seven people.

Numerous other sites, in Muslim countries, have also been offered as possible locations of the cave in the Qur'anic story. In Turkey (Ammuriyag Hadj Hamza: subterranean cave of an ancient Greek convent, and Tarsus; grotto), Syria (Damascus: the Ahl al-Kahf Mosque, with seven qibla in the crypt), Egypt (Cairo: cave of the Maghwari in Moqattam), in North Africa there are numerous sites. This attests only to how easy it is to find a cave, cemetery, and religious building situated in the same location.[29]

See Also

- Companions of the Cave - A hub page that leads to other articles related to the Companions of the Cave

External Links

- The Fellows of the Cave - Answering Islam (archived), http://www.answering-islam.org/Quran/Sources/s18.html

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Eich, Thomas. Muḥammad und Cædmon und die Siebenschläferlegende. Zur Verbindung zwischen Palästina und Canterbury im 7. Jahrhundert (abstract in English), Der Islam, vol. 100, no. 1, 2023, pp. 7-39. https://doi.org/10.1515/islam-2023-0003

- ↑ Reynolds, Gabriel Said. "Seven Sleepers" in Medieval Islamic Civilization, ed Josef W. Meri, Routledge, 2004, p. 720, ISBN 9780415966900

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Jacobus de Voragine, Archbishop of Genoa, 1275 First Edition Published 1470. "Seven Sleepers" in The Golden Legend: Volume IV (archived).

- ↑ The Latin text from M. Bischoff and M. Lapidge (eds.) (1994) "Biblical Commentaries from the Canterbury School of Theodore and Hadrian. Cambridge: Cambridge Univesity Press, pp. 416-419 is also quoted in Eich's article as a footnote to his German translation.

- ↑ Ibn Kathir, "The Story of the People of Al-Kahf" in Quran Tafsir Ibn Kathir, accessed December 3, 2013 (archived).

- ↑ Holly Hayes, "Cave of the Seven Sleepers, Ephesus", Sacred-Destinations, accessed December 4, 2013 (archived), http://www.sacred-destinations.com/turkey/ephesus-cave-of-the-seven-sleepers.

- ↑ For instance, one of the youths states, "Believe us, for forsooth our Lord hath raised us tofore the day of the great resurrection. And to the end that thou believe firmly the resurrection of the dead people, verily we be raised as ye here see, and live." (The Seven Sleepers: par 4)

- ↑ "Further, that He may warn those (also) who say, "Allah hath begotten a son":" - Quran 18:4

- ↑ "Is the trinity that the Christians believe in mentioned in Islam?", Islam Q&A, Fatwa No. 12713 (archived), http://islamqa.com/en/ref/12713.

- ↑ "The difference between the mushrikeen and the kuffaar, and to which category do the Jews and Christians belong?", Islam Q&A, Fatwa No. 67626 (archived), http://islamqa.com/en/ref/67626.

- ↑ Joseph A Islam, "The Sleepers of the Cave - The Quran, Historical Sources and Observations", The Quran and its Message, January 25, 2013 (archived), http://quransmessage.com/travelogues/seven%20sleepers%20FM3.htm.

- ↑ Lauren Everitt, Chi Chi Izundu, "Who, What, Why: How long can someone survive without food?", BBC News Magazine, February 20, 2012 (archived), http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-17095605.

- ↑ Dr. Alan D. Lieberson, "How long can a person survive without food?", Scientific American, November 8, 2004 (archived), http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=how-long-can-a-person-sur.

- ↑ Mahvash Vahed Doost, "Mythological phenomena in Ferdowsi's Shahnameh", Toos Publications, p. 389, 1989.

- ↑ Ibrahim Pour Davood, "Yashts. Ed. & Interpretation. 2nd vol.", Tehran: Asatir Publications, p. 77, 1998.

- ↑ 2 Maccabees Ch 7

- ↑ Albrecht Berger, Gabriela Signori (ed.), "Dying for the Faith, Killing for the Faith: Old-Testament Faith-Warriors (1 and 2 Maccabees) in Historical Perspective", BRILL, 2012, pp. 114-118, ISBN 9789004211056, 2012, http://books.google.com/books?id=ln5Db7iDHhMC&pg=PA117.

- ↑ D. L. Ashliman, "Sleeping Hero Legends", University of Pittsburgh, August 2, 2013 (archived), http://www.pitt.edu/~dash/sleep.html.

- ↑ Clive Foss, "Ephesus after Antiquity: A Late Antique, Byzantine and Turkish City", Cambridge University Press, p. 43, 1979.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 F. J. Hamilton, D.D. and E. W. Books (trans.), "Zachariah of Mitylene, Syriac Chronicle: Book II Chapter 1", M.A. Methuen & Co, 1899 (archived), http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/zachariah02.htm.

- ↑ Peter L’Huillier, "The Church of the Ancient Councils", Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, pp. 199-201, 1996.

- ↑ Richard Price and Michael Gaddis, "The Acts of the Council of Chalcedon vol. 3", Liverpool University Press, pp. 1-3, 2007.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Ernest Honigmann, “Stephen of Ephesus and the Legend of the Seven Sleepers,” in Patristic studies (Studi e testi), Biblioteca apostolica vaticana, 1953

- ↑ "Kahf Ahl Al-Kahf (Cave of the Cavemen)", Greater Amman Municipality, accessed December 5, 2013 (archived), http://www.ammancity.gov.jo/en/services/histdetails.asp?id=3.

- ↑ Palumbo, G., 1994. Jordan Antiquities Database and Information System. Amman: American Center for Oriental Research. Cited in: Jerome C. Rose & Dolores L. Burke, "Making Money from Buried Treasure", Culture Without Context, Issue 14, Spring 2004 (archived), http://www2.mcdonald.cam.ac.uk/projects/iarc/culturewithoutcontext/issue14/rose-burke.htm.

- ↑ Matthew Teller, "Jordan", Rough Guides, p. 106, ISBN 9781858287409, 2002, http://books.google.com/books?id=tI9L9gepYAUC&pg=PA106.

- ↑ Ghassan Taha Yaseen, "Qur’an and Archeological Discoveries: Evidence from the Near East", World Journal of Islamic History and Civilization, 1 (3): 201-212, 2011. ISSN 2225-0883 (archived), http://idosi.org/wjihc/wjihc1(3)11/7.pdf.

- ↑ Jerome C. Rose & Dolores L. Burke, "Making Money from Buried Treasure", Culture Without Context, Issue 14, Spring 2004 (archived), http://www2.mcdonald.cam.ac.uk/projects/iarc/culturewithoutcontext/issue14/rose-burke.htm.

- ↑ Geneviève Massignonn, "The Veneration of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus", 1963 (archived).