Huruf Muqatta'at (Disjointed Letters in the Qur'an)

This article or section is being renovated. Lead = 4 / 4

Structure = 4 / 4

Content = 3 / 4

Language = 4 / 4

References = 3 / 4

|

ḥurūf muqaṭṭaʿāt (حُرُوف مُقَطَّعَات), are mysterious letter combinations which occur at the beginning of 29 of the 114 chapters of the Qur'an and are present even in the earliest available Quranic manuscripts. Ḥurūf means letters and muqatta`āt literally means abbreviated or shortened. They are also known as Fawātih (فواتح) or openers as they form the opening verse of the respective chapters. The classical Muslim scholars considered the text of the Qur'an to be unchanged. Thus, they do not consider that the muqattā'at may possibly have been added after the prophet's lifetime, and proposed a variety of possible meanings for the letters. Aided by additional observations, modern academic scholars have proposed interpretations in which the letters are an original feature of the surahs, as well as suggesting theories in which the letters were added after Muhammad's death. The Muqatta'at continue to be a topic of research and academic discussions in Islamic literature and Qur'anic studies.

Introduction

In Arabic language, these letters are written together like a word, but each letter is pronounced separately. None of these combinations, however, come together to form a meaningful Arabic word. Still, these letters appear joined together in print.

A few examples of Muqatta'at

- 'Alif Lām Mīm - Surah Al Baqara, Surah Al Imran, and others

- 'Alif Lām Rā' - Sura Yunus, Surah Hud

- 'Alif Lām Mim Rā' -Sura Ar Raa'd

- Ḥā' Mīm - Surah Ha Mim Sajda

- Kāf Ḥā' Yā' `Ayn Ṣād - Surah Maryam

Of the 28 letters of the Arabic alphabet, exactly one half, that is 14 letters, appear as muqattā`at, either singly or in combinations of two, three, four or five letters. The fourteen letters are: أ ح ر س ص ط ع ق ك ل م ن ه ي (alif, ha, ra, sin, sad, ta, ain, qaf, kaf, lam, mim, nun, ha, ya. Notably, each of these letters has a unique rasm. (The apparent hamza in ك is a graphical device to reflect its original form, as does its variant ﻛ and its initial and medial cases, ﻛ and ﻜ, respectively.)

The letters are found even in the oldest Quranic manuscripts dating to the 7th century CE (occasionally with diacritical dots to disambiguate the letters Nūn in surah 68, Qāf in surahs 42 and 50, and Yā' in surahs 19 and 36).[1] This includes the lower text of the famous Sana'a palimpsest, which preserves very few surah openings, though includes the start of Surah Maryam with its five-letter combination included in the examples shown above.[2] Hence, the letters date back at least to the common ancestor of the palimpsest and the standard Uthmanic text.

Context

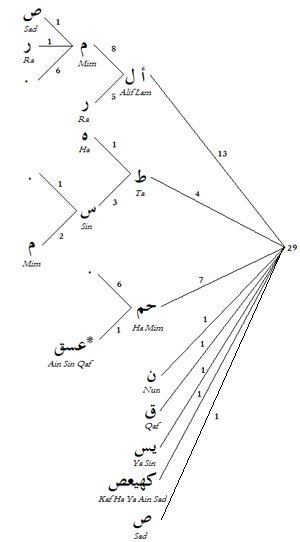

Certain co-occurrence restrictions are observable in these letters; for instance, alif is invariably followed by lam. The substantial majority of the combinations begin with either alif lām or hā mim. See the diagram for fuller information.

As noted by Muslim scholars, in all but 3 of the 29 cases, these letters are almost immediately followed by mention of the Qur'anic revelation itself (the exceptions are surahs 29, 30, and 68); and some, such as Yusuf Ali,[3] (tenuously) argue that even these three cases should be included, since mention of the revelation is made later on in the surah. More specifically, one may note that in 8 cases the following verse begins "These are the signs...", and in another 5 it begins "The Revelation..."; another 3 begin "By the Qur'an...", and another 2 "By the Book..." Additionally, all but 3 of these surahs are Makkan surahs (the exceptions are surahs 2, 3, 13.)

The surahs that contain these letters are set out in the following table:[3]

| Letters | Surahs |

|---|---|

| 'Alif Lām Mīm | 2, 3, 29-32 |

| 'Alif Lām Mīm Ṣād | 7 |

| 'Alif Lām Rā' | 10-15 |

| 'Alif Lām Mīm Rā' | 13 |

| Kāf Hā' Yā' `Ayn Ṣād | 19 |

| Ṭā' Hā' | 20 |

| Ṭā' Sīn Mīm | 26, 28 |

| Ṭā' Sīn | 27 |

| Yā' Sīn | 36 |

| Ṣād | 38 |

| Ḥā' Mīm | 40-46 |

| `Ayn Sīn Qāf | 42 |

| Qāf | 50 |

| Nūn | 68 |

Academic scholar Daniel Beck has further observed that when the surahs are sorted using the chronology proposed by Theodore Noldeke, 17 of the 18 occurances from the third Meccan period (and including the two occurances in surahs attributed to the Medinan period) are limited to combinations which comprise (or include) the letters 'Alif Lām Mīm, 'Alif Lām Rā', or Ḥā' Mīm. There is considerably more diversity of letter combinations in Noldeke's second Meccan period plus the sole occurance in the first Meccan period (the letter Nūn at the start of Surah 68, by far the earliest occurance).[4]

Classical Islamic Opinions

Many tomes have been written over the centuries on the possible meanings and probable significance of these 'mystical letters', as they are sometimes called. Opinions have been numerous but a consensus remains elusive. There is no report in the Ahadith or Sirat of Muhammad's having used such expressions in his ordinary speech, or his having thrown light as to its usage in the Qur'an. And, more importantly, none of his Companions seemed to have asked him, regarding it. This apparent lack of examples of this sort of inquisitiveness is cited as proof that the usage of such abbreviations were well known to the Arabs of the time and were in vogue long before the advent of Islam.

Some of the better known opinions are:

Alif Lām Mim stands for 'Anā Allāhu `ālim or I am Allah the All Knowing

Alif Lām Rā stands for 'Anā Allāhu Rā'i or I am Allah the Seer

The Companions Ibn Abbas and Ibn Mas'ud are said to have favored this view as cited by Abu Hayyan al Andalusi in his Bahr Al Muhit.

Though plausible, this opinion does not find favor among other classical commentators, the reason given being that the possible combinations of letters are virtually infinite and the Attributes they represent seem to be chosen arbitrarily

Modern Islamic Research

In 1974, an Egyptian biochemist named Rashad Khalifa announced he had discovered a mathematical code in the Qur'an based on these initials and the number 19,[6] which is mentioned in Quran 74:30 (However, Günter Lüling claims that the number is really 7, as in the 7 gates of the Christian Hell. See "Above it are neither nineteen nor seventeen"). According to his research, these initials which prefix 29 chapters of the Qur'an occur throughout their respective chapters in multiples of this very number, nineteen. He has noted other mathematical phenomena throughout the Quran, all related to what he describes as the "mathematical miracle of the Qur'an." Although subsequently dismissed as a heretic by Muslim scholars, his work did receive some acclaim by notable sources:

Scientific American of September 1980, p. 22. Martin Gardner wrote of Khalifa's initial publication in the West: "It's an ingenious study of the Quran,...Nineteen is an unusual prime. For example, it's the sum of the first powers of 9 and 10 and the difference between the second powers of 9 and 10."

Three years later the Canadian Council on the Study of Religion reported in its Quarterly Review of April 1983 that the code Khalifa discovered is "an authenticating proof of the divine origin of the Quran." Since 1983, little notice has been taken of this work.

Amin Ahsan Islahi stated that Arabs used to use such letters in their poetry and since Qur'an addressed them in their own linguistic style, it was only appropriate for Qur'an to use the same style. He agrees with Rāzi and mentions that since these letters are in some cases used as the names for their respective surahs, being proper nouns they are not bound to have a meaning. At the same time, he cites research from Hamiduddin Farahi, a Qur'anic scholar from the Indian subcontinent, on how these letters must be appropriately chosen according to the content and theme of the surahs.

Farahi links these letters back to Hebrew alphabet and suggests that those letters not only represented phonetic sounds but also contained a symbolic meaning to them, and Qur'an perhaps uses the same meanings when choosing the letters for surahs. For instance, in support of his opinion, he presents the letter Nun (ن), which symbolizes fish and Surah Nun mentions Jonah as 'companion of the fish'. Similarly, the letter Ṭa (ط) represents a serpent and all the Surahs that begin with this letter mention the story of Moses and serpents.[7]

Modern academic insights and interpretations

Daniel Beck observes that academic scholars commonly at first suppose that the letters conveyed textual information regarding the scribes or manuscripts used during the inital compilation process of the Quranic materials. Indeed, it is tempting to imagine the letters were the initals of scribes or an alphabetic index of small collections of surahs. Generally (like Noldeke), they abandon such a view when exposed to other considerations.[4] The main motivation for preferring to view them instead as features of the original recitation is the one mentioned above - the observation that the letters almost always immediately precede mention of the Quran or revelation itself. Other reasons include the observation that the letter combinations tend to rhyme (or near-rhyme) with the rhyming schema of the verses which follow them.[8]

Within this perspective, Beck explains that both early modern academic as well as Islamic scholars supposed that the letters were abbreviations for Arabic words whose referents were forgotten after Muhammad's death. The dominant view today among academic scholars is instead that the letters are not abbreviations for words (the "no referents" view), but rather convey the idea of Arabic letters or its alphabet in some mystical sense, a kind of mantic performance, akin to chanting "abracadabra" or ABC 123 in English. Beck challenges this view due to the lack of late antique precedent and the pattern noted above wherein there is a lack of diversity of combinations in the third Meccan period as well as other observations such as the strong concentration of occurances in that period and an almost complete cessation thereafter. Beck's own proposal is a referents theory associated with the needs of a certain period leading up to Muhammad's political ascendancy.

Other observations by historical-critical academic scholars include:

1. The muqatta`āt are already present in the earliest Quranic manuscripts (as noted in more detail above).

2. The rasm of each of the muqatta`āt is unique.[4] In the case of ي, it is only found initially, so its rasm is unique, too. Except for ي and ن, each letter has no dots. In the case of ن, the dot is usually omitted in handwriting in the final and isolated cases.

3. The final six letters of the Arabic alphabet (in the 'abjad' sequence) are not used.[4]

4. The muqatta`āt are not distributed at random. 'Alif Lām Mīm occurs in two consecutive sets of surahs: 2-3 and 29-32 (and 'Alif Lām Mīm Ṣād in sura 7). Between these ranges, 'Alif Lām Rā' occurs in the consecutive surahs 10-15. Ḥā' Mīm occurs in the consecutive surahs 40-46. Ṭā' Sīn Mīm occurs in the non-consecutive surahs 26 and 28. However, if Ṭā' Sīn is really Ṭā' Sīn Mīm, then the latter also occurs in consecutive surahs.

These other points on their own would seem to be supportive of theories linking the letters to the initial compilation of the scripture; perhaps the initials of the scribes who worked to make the original copy of the complete Quran (a theory slightly complicated by the presence of two sets of muqatta`āt in Surah 42), or some kind of filing system for the source parchments, although it is to be noted that when the Quran was compiled into a single book a general sequence of longest to shortest surahs was used (a method employed also in other late antique literary compilations). The source materials for the muqatta'at surahs would not likely each have contained only surahs of similar size such that their sequences would be largely maintained in the compiled Quran. It has at the same time, however, been noted that the consecutive sequence of Ḥā' Mīm surahs (which are even consecutive in the reported non-standard surah sequences of early Companion codices) form a clear literally unit with similar themes.

See Also

References

- ↑ For discussion and images see this Twitter.com thread by Quranic manuscripts academic expert Marijn van Putten - 8 December 2021 (archive)

- ↑ See line 24 of Folio 22 A transcribed on page 63 in Sadeghi, Behnam; Goudarzi, Mohsen (2012). Ṣan'ā' 1 and the Origins of the Qur'ān. Der Islam. Berlin: De Gruyter. 87 (1–2): 1–129. doi: 10.1515/islam-2011-0025

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Based on Yūsuf `Alī's discussion in Appendix 1 of his translation of the Qur'an (p. 124): Yūsuf `Alī, `Abdullah, The Holy Qur'ān: Text, Translation and Commentary, New Revised Edition, Amana Corporation, Brentwood, MD, USA, 1989. ISBN 0-915957-033-5

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Daniel Beck (2020) Reconnecting Al-Ḥurūf Al-Muqaṭṭa'āt To Oracular Truth-A New Chronological Analysis of the Qur'ān's Mysterious Letters"

- ↑ Michael R. Rose; Casandra L. Rauser; Laurence D. Mueller; Javed Ahmed Ghamidi, Shehzad Saleem (July 2003). "Al-Baqarah (1-7)". Renaissance.

- ↑ Rashad Khalifa, Quran: Visual Presentation of the Miracle, Islamic Productions International, 1982. ISBN 0-934894-30-2

- ↑ Islahi, Amin Ahsan. Taddabur-i-Quran. Faraan Foundation. pp. 82-85, 2004.

- ↑ Devin Stewart, "Notes on Medieval and Modern Emendations of the Qur'an." Pp. 225-48 in The Qur'an in Its Historical Context. Ed. Gabriel Said Reynolds. London: Routledge, 2008. See p. 234.